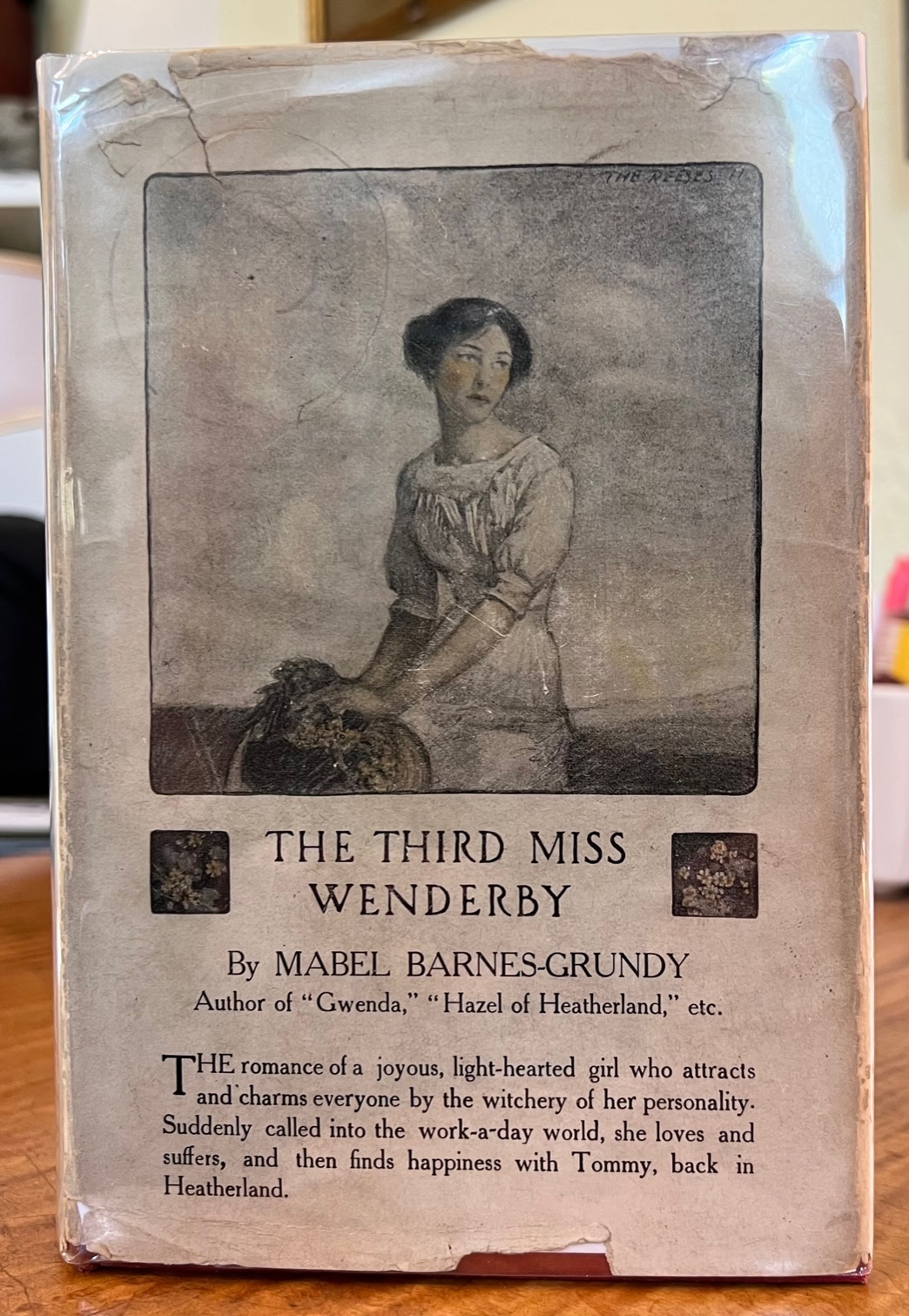

The Third Miss Wenderby

Mabel Barnes-Grundy

The Baker & Taylor Co., 1911

The Third Miss Wenderby

Mabel Barnes-Grundy

The Baker & Taylor Co., 1911

Description

[from review in The Courier-Journal (Louisville Kentucky), Sat Jan 13, 1912]

The Third Miss Wenderby is introduced to the reader at the age of seven, at which tender period she is described as having been the victim of an acute religious mania which manifested itself in a desire to commit some heinous sin in order to be a proper subject for divine redemption. The earlier pages of the book are more than ordinarily interesting in their description of the doings of the little "Diana," but the later adventures of that young lady do not make any very strong appeal either to the emotions or the imagination. Following the plan of an infinite number of novels of this class, the story is that of a well-to-do family suddenly impoverished, the daughter seeking that ever-ready refuge of the young English gentlewoman, and becoming a governess. The fact that she cannot even solve a simple problem in long division does not seem to be a deterrent. Most of the women, except the heroine, are more or less peevish and objectionable, with interesting husbands and other male relatives whom they do not understand. As Diana has a "God-given faculty of understanding men," she proves a valuable addition to society in various phases. She falls in love with the wrong man, but his perfidy is discovered in time to prevent her from being made permanently unhappy, and, in the end, of course she marries the long-suffering and persistent lover of her childhood days. It is eminently a book for "the young person" -- unless those specimens of humanity have ceased to exist.

Notes

It's no secret that I'm a big MB-G fan. Her writing is strong and I love her quirky, prickly heroines and the way she confidently inserts her views on all sorts of issues only tangentially related to the story.

That said, Miss Wenderby is one of her earlier efforts and, I'm inclined to agree with the Kentucky critic above, not her most appealing one. I think her female main characters work better in the first person where their unreliable narration is reliably amusing and where you really sit with them in their frustration with social rules and conventions that make no logical sense: most especially, the limitations the world places on them for the sole reason of their being born women. The third person is less effective in this project, especially here where the narration consists significantly of men's paeans to the exquisite, transporting "fineness" of the main character -- a girl who is lovely and spirited, yes, but not especially talented, frequently thoughtless, and forthright to the point of being rude. The first time Diana's employer, Mr. Poppleton sees her, he's stunned:

And the face of the girl! Not so beautiful as so fine, so unusual, so extraordinarily vivid and alive. This girl lived every moment of her life. Even in her dreams, the soul must leave the body, Mr. Poppleton felt, and wander away in search of fresh experiences, only to return when the body regained consciousness and another wonderful day was to be lived through....Shake hands! When he had much ado to keep from falling to his knees and apologizing to her for employing her as his governess at all. (210)

The hundredth passage from the dozenth man like that and you end up reluctantly sympathizing with the unfortunate Mrs. Poppleton who finds herself "too tired with everybody" (414) to care what they think or do.

As the review suggests, and unlike her other book, she also takes a really jaundiced view of a lot of her female characters in Miss Wenderby (and a flattering one of her male ones) and she spends a lot of the book dwelling on their narrowness, limitations and affectations -- especially compared Diana and their husbands (who can't help but admire her more). This jars with, and undercuts, her otherwise pro-woman stance. It's a peculiar choice. She indulges in her penchant for last-act killing off characters, too, though, at least, here, it's neither lead. But, on the upside, there's also a visit, near the end, to her beloved Mentone -- it would scarcely be MB-G without someone riding a donkey!

Miss Wenderby's certainly not all bad: good writing, as usual, and there's some thoughtful exploration of what makes a marriage work, a brief but welcome pro-union message, and a pretty, if somewhat melancholy take on coming of age as passing through the sorrow ("and then the rain descended") and the test of "life" ending and "existence" beginning: of going from "being" to "doing".

For similar themes done better try Sally In A Service Flat.

Flags: N-word used in the usual expressions and an interracial marriage portrayed as shameful.

Tags

1910-1919, English, Europe, England, I'm not good enough for you, already taken, beautiful/handsome, brave, courageous, charming, cheerful, clever, coming of age, determined, difficult child, disappointed in love, disciplined, eccentric/quirky/neurodivergent, f/m, family home, family, older relative, cantankerous, family, older relative, delightful, family, parent, responsible for, female, girl/boy-next-door/childhood playmates, governess/paid companion, hair, dark, heir/heiress, hot-tempered, humorous, idealistic, injury, intelligent, kind, love someone else, lovers, friends to, lovers, neighbors to, lovers, spoiled for choice, loyal, poor, poor little rich girl/boy, principled, rich, romance, saving the family home, secret past/my lips are sealed, selfish, selfless, single, spirited, tall, thin, third-person, tortured, unrequited until..., young

Flags

body negativity, insensitive or outdated language (race/ethnicity/disability/sexual orientation), racism