The Africa Run

Lucilla Andrews

Heinemann, 1993

The Africa Run

Lucilla Andrews

Heinemann, 1993

Description

[from inner dust jacket flap] It's summer 1955 and three people who were wartime friends are appalled to find they are fellow travelers on a small, old British passenger liner on the ten-week round-Africa run. Elinor Mackenzie is in tourist class. She was twenty-two when she was widowed during the war, but now, thirty-three, she is determined to start a fresh life for herself. In first class is Dr. Paddy Brown, sailing round Africa to convalesce from the polio that has pole-axed his intended marriage and his soaring medical career. George Ashden, ex-GP., is traveling to a new job in Rhodesia. Recently widowed, he is still haunted by his unhappy marriage -- and the memory of Elinor in 1945.

It is only in the Suez Canal that Paddy finally discovers the secret which Elinor has known since Genoa. And in the burning heat of the un-airconditioned ship in the Red Sea his action forces the three old friends into the inescapable proximity of passengers in the same class.

Swinging between two vanished worlds: daylightless, bombed, wartime London and the brilliantly sunlit decks of the liner and its exotic ports of call, The Africa Run is a most engrossing, memorable and evocative love story.

Notes

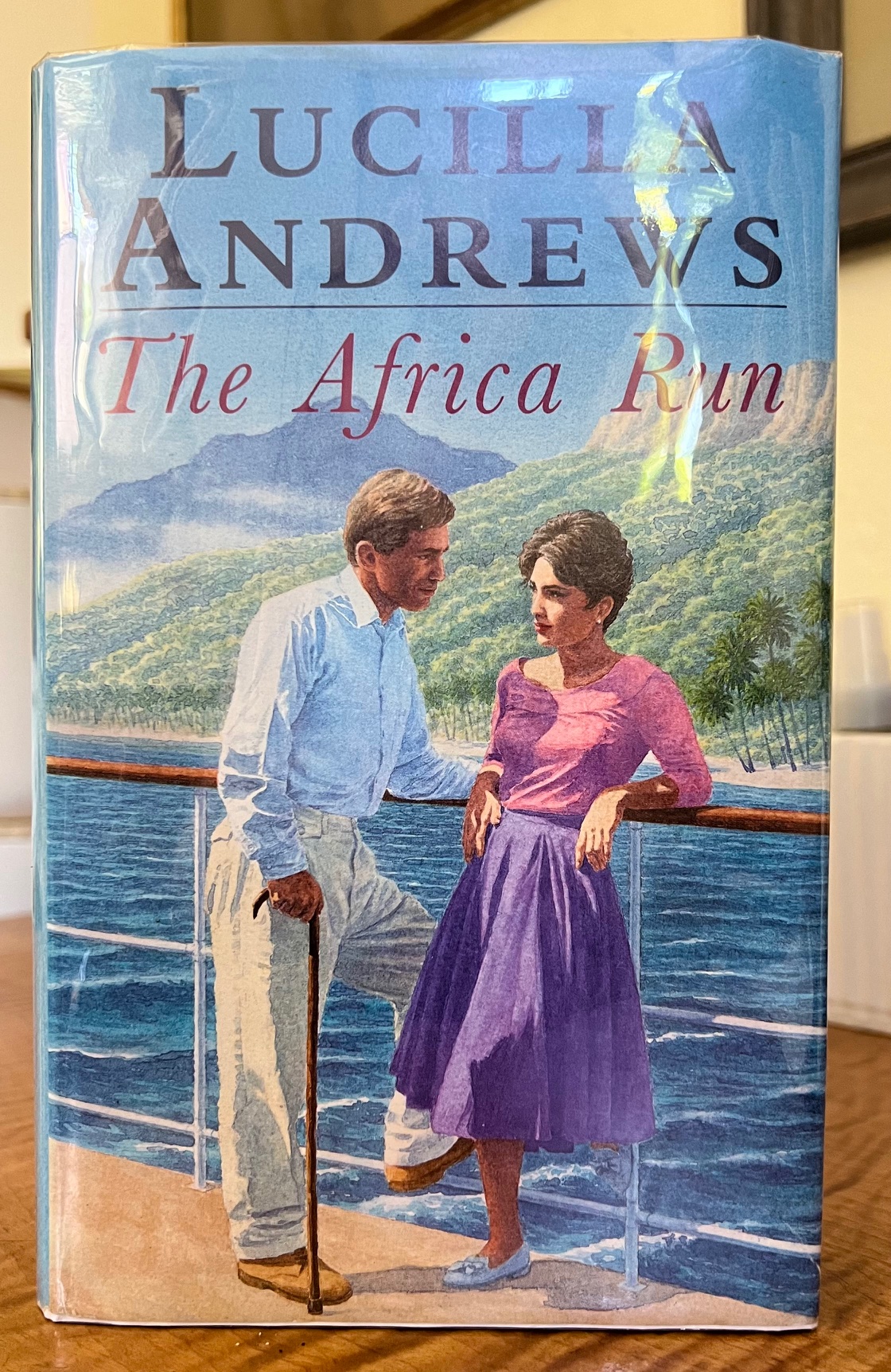

I really debated including the dust jacket in the book photo. It's one of those awful 80s/90s pastel watercolor numbers with no attempt at historical accuracy and zero resemblance to the character descriptions. Mike Embden was a talented British landscape artist and a popular fantasy illustrator in the 70s and 80s but, from what I've seen, his romance covers are pretty much travesties. I include it just for authenticity — I encourage you to divert your eyes & take a chance on The Africa Run. It’s absolutely worth it.

Lucilla Matthew Andrews Crichton was one of the dominant voices in British romance writing in the mid-20th century and the undisputed mother of the doctor-nurse sub-genre. She was born in Egypt in 1919 and educated in England. She joined the VAD in 1940, and trained and worked as a nurse in St. Thomas’s Hospital in London (it would become St. Martha’s in her books). She started writing in 1949 when her doctor husband was hospitalized for drug addiction. With a newborn to provide for, she worked night shifts as a nurse and wrote during the day. Her first novel, The Print Petticoat, was published in 1954; her husband died the same year. She would go on to write thirty-three romances and a number of mysteries (under the pen names Diana Gordon and Joanna Marcus). In her entry on Andrews in the indispensable Twentieth Century Romance and Gothic Authors (1982), Elizabeth Grey relates how Andrews’ “grim experiences” in the wartime wards informed her style and content — “She pulls no punches: readers’ noses are positively rubbed in medical fact — often gruesome.” Her popularity and medical axe-grinding had real-world effects: “A week after she described the results of a motor-bike accident in Woman’s Weekly the sale of skid-lids soared.” Andrew’s 1977 memoirs of her wartime service, No Time for Romance: An Autobiographical Account of a Few Moments in British and Personal History was heavily lifted from — some have argued, plagiarized by Ian McEwan in Atonement.

The Africa Run was Andrews’ last doctor-nurse romance and the final book she published under her own name. She was 74 in 1993 and The Africa Run, like several of her later novels, is really a meditation — from the distance, and with the grace, of her years — on what the Second World War, that cataclysm that had caught them up in their youth, did to her generation: what they lost and what they salvaged and how it left them changed, and marked, and set apart. Elinor and Paddy are still so young — she’s 33, he’s 37 — but they’re damaged people trying to put themselves back together — he, literally, after a bout with polio that left him partially paralyzed, and Elinor, in the face of her husband’s death in a Japanese internment camp and the realization that she will have to chart her way forward alone. Their wartime experiences at St. Martha’s, presented in flackback, serve both as an invisible thread drawing them together and a dam of painful memories — of exhaustion and disillusionment, and despair — the “catching on that there were no fairies at the bottom of the garden” (40) — that they at first can’t bring themselves to breach. There’s no games, no stupidly implausible misunderstandings here: what Andrews’ characters have to navigate on board the Rose of Africa is their own trauma, their own healing, and the way love might find a place in that. It’s a mature sensibility and a thoughtful, gentle, wise study on the slow unfolding of hope. This isn’t the first of her books to visit those themes, but what’s interesting about The Africa Run is that these very small, personal journeys of mourning and of coming to terms are set against the backdrop of the post-war geopolitical changes that already by 1955, where the book’s “present-day” is set, and overwhelmingly by the time of its writing, would force British citizens into a reckoning with their country’s past and a redefinition of their place in the world. The Africa that the Rose sails around is on the edge of a seismic shift — the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya is a carefully avoided undercurrent to the after-dinner conversation in the first class lounge — and the more astute passengers — Elinor, Paddy, and the older, wealthy and sharply observant American widow Mrs. Mellor — understand only too well that the ships’ traditions, the “standard of luxury and super-abundance”, the bridge in the lounge, the black-tie evenings ashore are all exercises in “dining with the ghosts of the Empire.” (128) There is a sadness these more intelligent, more removed observers feel for the older white settlers who move obliviously on towards loss, but much more than that is an honest reflection on what horrors the Empire has wrought on the native peoples it conquered and ruled — Elinor and Paddy both react with revulsion to South Africa’s Apartheid (still in effect at The Africa Run's publication) and the racism they witness among fellow passengers and on shore trips. Andrews is also clear-eyed about the price of Empire to the British themselves: Elinor’s family’s was broken, like Andrews’ by distance (British parents in the pre-vaccine era sending their children to boarding school back home as early as possible) and death (the staggeringly high rates of infant — and adult — mortality in India and Africa during this era).

Andrews’ critique of British tradition extends back into home and heart as her characters also consciously reassess what their generation's gender roles and norms — early marriage, sexual double standards — had cost young women, and Elinor makes a courageous decision about her future.

The realization Andrews’ characters ultimately come to is that, though the portion of their youth has been a heavy draught of sorrow and regret, survival is a gift, and not all change is bad: Empires should crumble. Ideologies should evolve. People should grow. And happiness, maybe, is savored more — in “gratitude and wonder” (217) — for knowing that “it is no birthright, but a loan”.

Wonderfully detailed descriptions, in the flashbacks, on hospital life under bombardment and an awed appreciation for the “avalanches” that had just rocked the world of medicine: “penicillin in ‘44; the antibiotics in ‘48”, “tubercule…hit on the head” and the “Yanks” seeming “to be on to something” (17) re. polio.

Not a light story — look to her earlier doctor-nurses for that — but a satisfying, grown-up, melancholy-but-hopeful read. (Just hide that jacket!)

Tags

1940s, 1950s, 1990s, Africa, English, Europe, England, Irish, beautiful/handsome, brave, courageous, competent, determined, disabled, other, doctor, efficient, escape old life, f/m, fake marriage, fashionable, female, flashbacks, forced proximity, hair, dark, heir/heiress, independent, intelligent, lovers, friends to, lovers, spoiled for choice, modern medicine, miracle of, nurse, ocean liner, practical, principled, progressive, recommended, romance, single, strong, tall, thin, third-person, widowed

Flags

insensitive or outdated language (race/ethnicity/disability/sexual orientation)