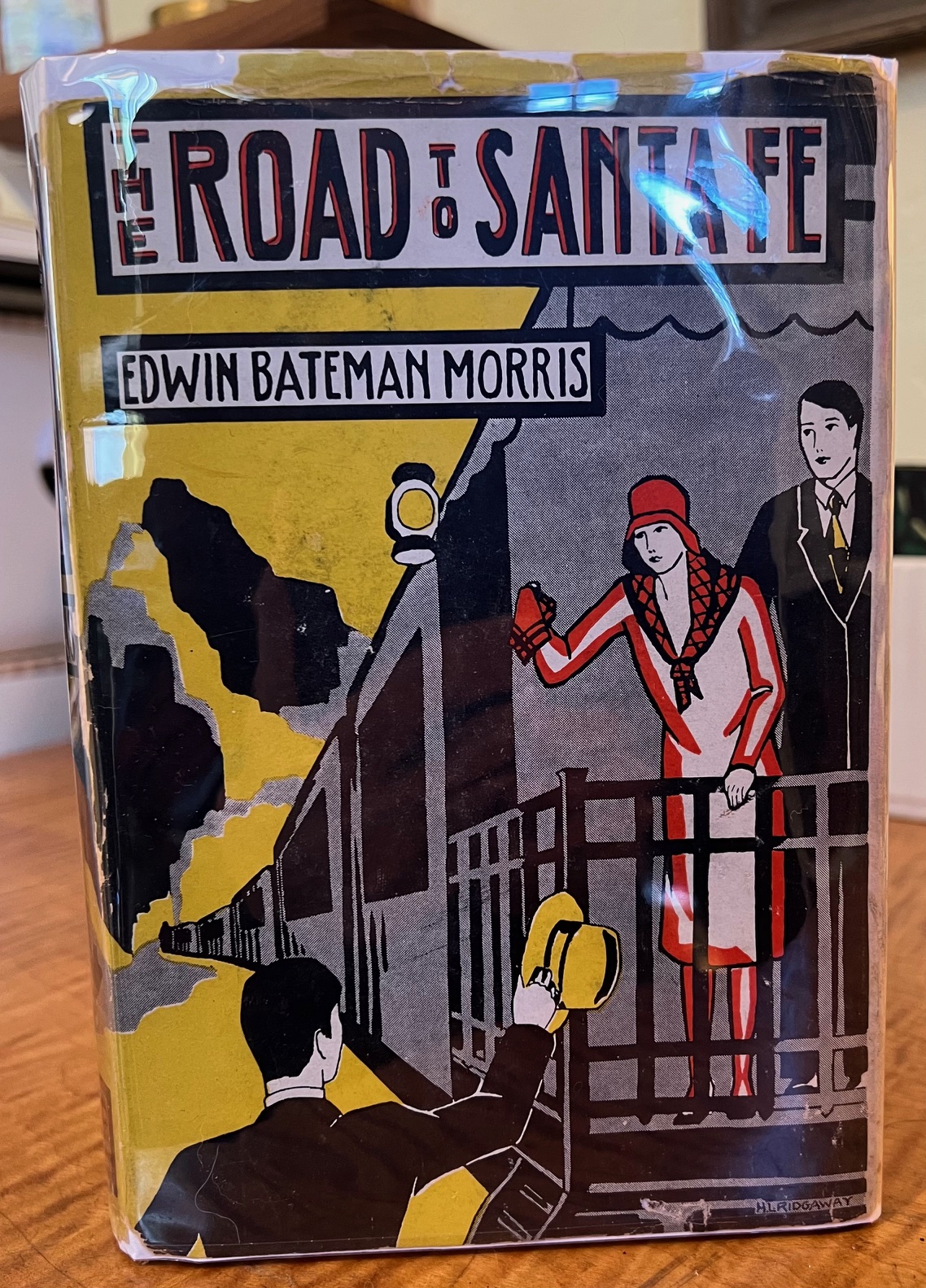

The Road To Santa Fe

Edwin Bateman Morris

The Penn Publishing Company, 1930

The Road To Santa Fe

Edwin Bateman Morris

The Penn Publishing Company, 1930

Description

[from inner dj flap] In this day of aggressive, pursuing females, there is little promise for the girl who is old-fashioned enough to wish to be the pursued. Claire Severn finds it difficult to compete with her own sex or yet to see enough of her admirers to judge of their sterling qualities. So she arranges a railroad journey across the United States on which she is accompanied, in succession, by four of the most promising of her suitors. Though the trip is disillusioning and each candidate is a disappointment, Claire does find her ideal man -- but in an entirely unexpected quarter.

Notes

Edwin Bateman Morris, like many of these early popular writers, was a busy guy. His day job was as an architect for the federal government -- initially, in the Treasury Department, and then as assistant supervising architect in FDR's US Public Buildings Administration (PBA). During this period, he "edited The Federal Architect, an urbane periodical for those who had known the drudgery and delight of carrying out Uncle Sam’s building program" (Stokes, U Chicago Press Journals, 2014, online here) and wrote a dozen or more light, comedic plays and novels -- including one, The Narrow Street, which was filmed by Warner Bros. in 1925 and "[later] had the distinction of being one of the first silent pictures to be converted into a 'talkie'" (Wide Open, 1930, starring the wonderful Edward Everett Horton). "Such is the dual personality of versatile Edwin Bateman Morris," begins a Feb 15 1934 profile in Washington D.C. Evening Star, "who uses his talents in each of these diverse fields of activity to refresh him for the other."

All this preface is not just to repeat a point I've made before -- namely, that romantic writing aimed at a female reader hadn't yet been pink-collared during this period -- or even to celebrate Morris's creative energy, which appears to have been prodigious -- but because it's important background to really appreciating The Road To Santa Fe. A la the Williamsons, but with a lighter hand, The Road To Santa Fe is part romance, part travelogue. Over the course of the book, our heroine, Claire, and her erstwhile suitors journey from Chicago to Santa Fe aboard "The Chief", an "Extra Fine-Extra Fast-Extra Fare" (one night Chicago to LA!) long-distance passenger train which ran from 1926-1968 and "became famous as a "rolling boudoir" for film stars and Hollywood executives" during that period. If you have endured Amtrak's "Southwest Chief", you know the scenery if not the luxury -- per Wikipedia, it's the only train still servicing that route.

As his characters rolled, so too, it quickly becomes clear, did our architect-author. What we get a lot of throughout their/his journey, is descriptions of (and opinions on) architectural points of interest within a short walk of the train stations from Chicago southwest. Many of these sites still exist but several of the more commercial ones are lost, so following along online makes for a fun visual trip courtesy of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway circa 1929.

For your traveling pleasure, the conductor would like to point out:

- Fountain of Time and Chicago's outer lake drive (78)

- National World War Museum and Memorial in Kansas City (103)

- Dodge City sundials in Dodge City, Kansas (110)

- El Ortiz Hotel in Lamy, New Mexico (115)

- La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, New Mexico (131)

- The Castañeda in Las Vegas, Nevada (145)

- The Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, New Mexico (179)

- San Felipe de Neri in Albuquerque, New Mexico (186)

- Puye Cliff Dwellings in the Santa Clara Canyon, New Mexico (269)

And I'm sure I missed some! Morris has strong views on these sights, and what they represent about America and their region. It's interesting and almost nostalgic to hear America, through the lens of public architecture and art, envisioned as "the young strong giant , whose blood coursed through him, urging deeds, ideas -- Virility and inspiration -- they went hand in hand." (76) -- rather than the bloated, late capitalist empire it often appears today. He also has opinions on the rising generation of architects, and skewers one of the young suitors, portrayed as a pompous, humorless young example of that profession, with malicious glee. Coming across the Santa Fe post office "with its gentle appreciation of art and beauty", young Witmer turns up his nose "A pure Santa Fake!" (136) "That's the whole town!...Pretty! Something for a glass case!" (138) Claire closes "a full day of Witmer" depressed and with "a cerebral toothache, which put her in the mood to throw hard objects through big mirrors." (179)

The travelogue part is, actually, the strongest part of the book. The romance would have been better had Morris been able to convey Claire's inner life as well as he does that of her eventual choice of partners. He, the male mc, is kind, intelligent, somewhat shy and unkempt, but capable, principled, unselfish -- reflecting to himself "But that was life. You took from your own store of comfort to give to others. It was your tax for being in the world." (131) -- successful, yet modest,"Cursed at birth with that facility for self-inspection that showed one's ambitions to be far beyond his actual grasp" (229). He's wholly likeable and you're in his corner from the start. Claire, meanwhile... Morris has to tell the reader outright, and repeatedly, that "she had the charm which the mere passage of years could never dull" (229) to explain her attraction (beyond her wealth) to all these young men because he never really shows this to you at all.

That said, it's an entertaining, and, on occasion, unexpectedly thought-provoking, read. His take on gender roles and profession, for instance, is that you are fundamentally constrained in both by the generation of your birth and the historical & cultural conditions of your moment on the world stage. In the late 1920s and early 30s, he felt, the world was "changing into something different" and the young people coming of age were traversing interesting, uncomfortable times. His view was that gender roles had swung widely in the past few decades -- with girls now the pursuers -- "let the magnet seek the man" (12) -- and their romantic prospects pampered and coy -- "That was the diverting thing about young men -- you never knew whether they would be there or not. Their charm lay in their unexpectedness, their strange and fitful impulses, their airy surrender to whim." (102) Claire is an old-fashioned girl -- she wants to be pursued -- but she is reduced, by the unspoken social laws of her generation, to being the one actually orchestrating the whole series of railway "meet cutes". Morris, through his male main character, predicts the pendulum will swing somewhat back. And, though I don't totally buy that role reversal depiction of 192os dating, considering the regression that women's progress would experience in the 1950s, it's hard not to see his pendulum bet as painfully apt. Much happier to consider is his staunch belief that changes in young women's dress and attitudes are "just a detail" (241) -- and that a young woman is equally admirable with bare legs and an assertive character to her "three-petticoated" sister of an earlier era.

Also, and always, the slang! A pretty girl as "A right sharp young frail." (11) "The bunk" = very poor. "The nuts" = superlatively good. "It gripes my soul." "Pep, Youth, It." It's just so fun.

Tags

1930s, American, United States, Southwest, age difference, athletic, competent, determined, eccentric/quirky/neurodivergent, employer/employee, executive, f/m, heir/heiress, intelligent, lovers, spoiled for choice, male, old-fashioned, on the road, opposites attract, orphaned, plain, poor little rich girl/boy, practical, principled, protector, rich, romance, single, third-person, train, travelogue, vacation, young

Flags

None